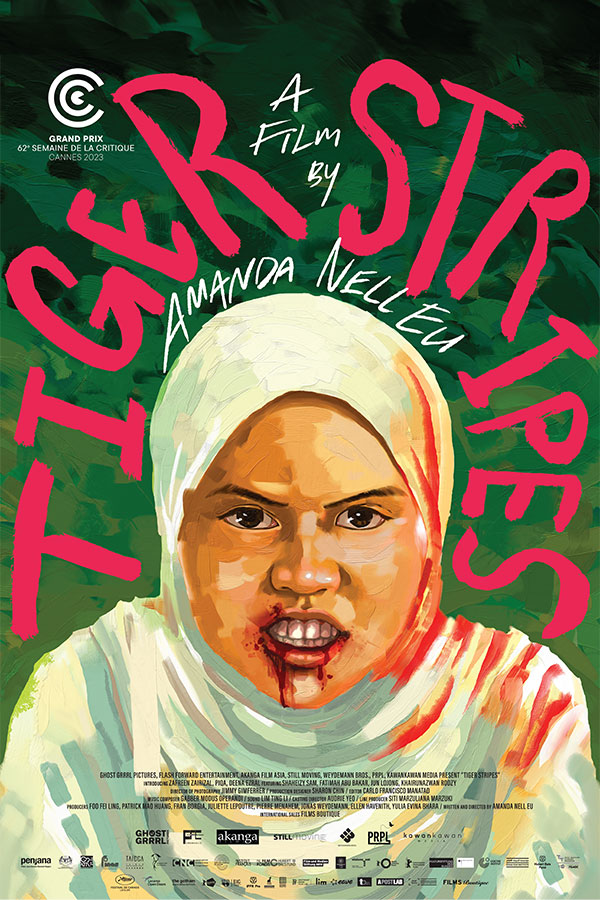

This is Engelbert Rafferty’s return to Film Police Reviews! He writes about Amanda Nell Eu’s directorial debut, ‘Tiger Stripes’. The film is also the recipient of the Pylon Award for Asian Next Wave Best Picture and Best Director in this year’s QCinema International Film Festival.

The Philippines and Malaysia are neighboring countries. As Filipinos, we have always been directly associated with the Malay, if you flip the pages of history books. It’s no wonder at this point that – difference aside – we bear similarities with the Malay in terms of food, culture, identities, behavior etc. Heck, we can even be mistaken for one another through the mere colors of our skin (because we live in the Equatorial part of the globe). One perfect example I can think of at the top of my head in terms of Filipino folklore is the manananggal – a mythical creature, often depicted as feminine, that can split its torsos in half at will, constantly searching for sleeping pregnant women to siphon their fetuses – and how this is very much similar to the Malay penanggalan, only the latter hunts down menstruation blood or blood excreted from mothers giving birth. Speaking of menstruation, no matter where you go, this subject matter is taboo on a universal level. It has been throughout history. While we may not be able to discern when it was first considered taboo – reasons ranging as absurd as the blood emanating evil supernatural spirits to as scientific as the first menstrual trigger (called a menarche) causing blood clots around the chambers of the heart – which we know now to this point that is false.

In Amanda Neil Eu’s debut feature Tiger Stripes, we see both subject matters discussed by way of “period” body horror. The film chronicles Zaffan (played by Zafreen Zairizal) as she reaches full puberty in a rural area in Malaysia. At first, we see Zaffan with her friends Farah (played by Deena Ezral) and Maryam (played by Piqah) navigating through their not-so-mundane day-to-day by causing mischief in the bathroom of the all-girls school they’re enrolled in, by playing random games that spring up the top of their heads while in a nearby pond, or even by telling stories to each other about scary incidents that happened in their community’s past (whether these stories be true or not). As these characters’ personalities get built right in front of us, Zaffan at one point in the start of the film experiences excruciating discomfort and gets a taste of her first period – where everything takes a turn for better or worse.

Neil Eu uses the body horror and coming-of-age genres to capture the growing pains of puberty. Keep in mind that this approach is far from novel, as we have seen said approach in numerous films in the past. Think John Fawcett’s Ginger Snaps, a movie about two outcast sisters in a suburban neighborhood, which depicts the terror and madness of female puberty and teenage sexuality through the use of the werewolf fantasy; or perhaps even, more recently, Domee Shi’s Turning Red, a movie about an awkward Chinese girl growing in an urbanized space, which makes use of animation and comedy for people to see and feel the Asian-Canadian experience of growing up as a teenage girl most especially during your first “periodic” moment. And yet, with Neil Eu’s film, the depiction of the feminine adolescent body dysmorphia feels innovative. She uses local colors to bring forth a sense of familiarity and nostalgia to her audience that still somewhat feels universal. She makes use of varying aspect ratios to provide and indicate the gaze the film intends to present (such as the use of vertical video to present the gaze of social media through the perspective of the teenage girls etc.).

Speaking of local colors, what really sets the film apart from its aforementioned counterparts is its use of metaphorical language. Neil Eu’s writing speaks for itself: portraying mass hysteria through the students and teachers as means of erecting the taboo nature of menstruation in the local community, using the rural area as means of showcasing the fixed mindset brooding in these communities due to lack of awareness (or education, which is an irony in itself considering how majority of the scenes are within school premises), depicting growing social structures between the seniors and the juniors through the color of their attire (which may not be intentional and more of an actual situation in some schools in Malaysia). In particular, the use of the Malayan tiger in this film is razor sharp – as Zaffan metamorphoses into the said animal, she slowly starts living an isolated existence perhaps to capture the loneliness of a growing girl’s dilemma. As she slowly feels the need to disconnect, the concepts of boundary, privacy and safety become clear as day in her mind and she uses the jungle as her safe haven, away from the need to adapt in the social hierarchy. In her isolation, she finds difficulty in expressing her problems to anyone and, in turn, her actions get misunderstood by everyone, including her parents.

Venturing into the heart of Tiger Stripes, we the audience get pulled on a cross-cultural odyssey that transcends geographical borders. Set against the backdrop of Malaysia and drawing from the wellspring of Malay folklore, Eu’s film not only captures the essence of a culture but also resonates with echoes from across the seas, notably in the shared threads that connect Malay and Filipino traditions, making use of topics that are not only controversial by nature but also calls for a needful education that transcends racial, social, or even perhaps cultural differences. Eu, with her use of audiovisual language, artfully portrays the universal theme of female adolescence, using the lens of a teenage girl’s first period to illuminate the nuances of growing pains by way of body horror. Through this exploration, Tiger Stripes emerges as more than a film; it’s a cultural bridge, a testament to the shared human experiences that unite us all, regardless of our cultural or racial backgrounds.

Reviews from other members:

John Tawasil

We first see Zaffan (Zafreen Zairizal) recording a Tiktok dance in a bathroom with her friends. She’s a bit of a free spirit, flouting the school rules and jumping into rivers, much like any child. One day, however, Zaffan has her first period and her body starts to change. She sees someone in the trees that no one else can see, and she begins to act out ferally. She is turning into a harimau jadian, or weretiger.

In her seminal book The Monstrous-Feminine, Barbara Creed writes about how the prototype of the monstrous in all forms of media is the female reproductive body. In her discourse regarding Brian De Palma’s Carrie (1976), blood – specifically, the blood related to menstruation – is linked to her supernatural powers. As a ‘witch’, she “… sets out to unsettle boundaries between the rational and irrational, symbolic and imaginary.”

Folklore has long used a fear of the feminine to imagine its monsters. There’s the pontianak who lives in trees and eats passersby, especially men. There’s the manananggal who splits her body at night to hunt for food. Then there are the many spirits and demons in Japanese folklore, women wronged in some fashion and made to seek revenge against those who wronged them.

Yet in modern society, there seems to be no boogeyman so terrifying to men (and even women, as manifestations of internalized misogyny) as that of femininity itself. The harimau jadian is no less feared as that of the teenage girl, femininity as a monster that needs to be controlled and suppressed. Director Amanda Nell Eu ties the bodily transformations of puberty with the supernatural transformation of man to animal, and this brings out fear in those who do not understand. In Tiger Stripes, Zaffan is subjected to all sorts of humiliation and trials simply because she has her period. By custom, she is unable to pray because her menstrual flow is unclean. She is bullied and ostracized by her peers because of it; Farah (Deena Ezral), her former friend, is the ringleader, though this disgust is learned – she picked it up from her father, who reacted negatively when Farah’s sister inadvertently bled on the family sofa.

In real life, the film struck a nerve among conservatives, who censored the film to remove images of blood and unabashed femininity. Even in the real world, there is an undercurrent of fear regarding women and women’s bodies, no ‘monster’ so feared. Yet these are just young women just coming of age, living their lives. To me the end scene communicates that: as they pass from children to young adults, they are treated as monsters, but they are no different in essence to who they were before – human beings capable of happiness, friendship and even love.

This review first appeared on Present Confusion.