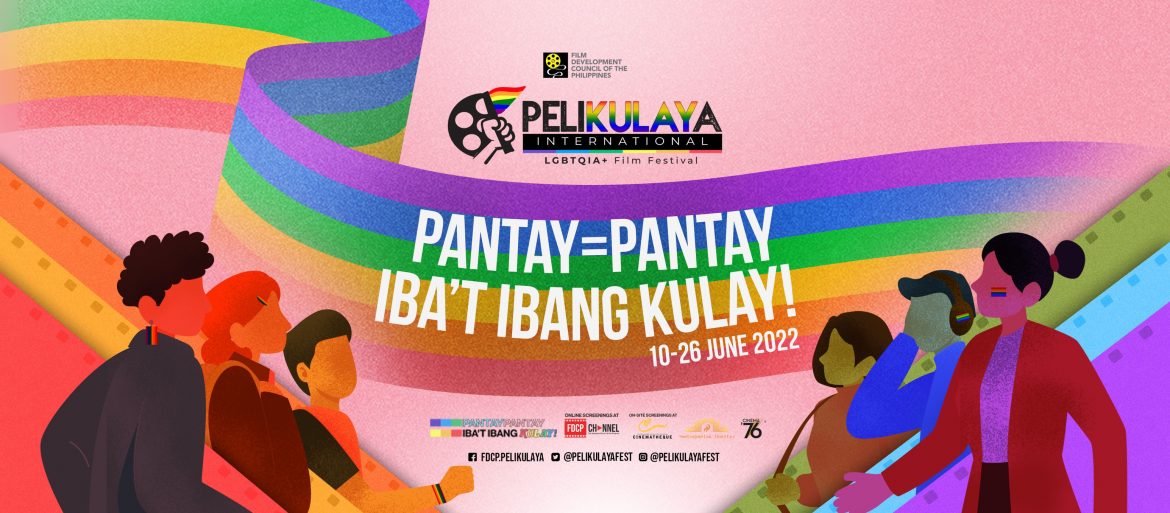

In its third year, Pelikulaya, the international LGBTQIA+ film festival organized by the Film Development Council of the Philippines (FDCP), holds a hybrid format. Coinciding with the Pride Month celebration, the festival offers a slate of local arthouse films and internationally acclaimed titles, such as Ishmael Bernal’s Manila by Night, Isabel Sandoval’s Lingua Franca, and Céline Sciamma’s Portrait of a Lady on Fire.

Apart from virtual and in-person screenings, roundtable discussions are also conducted, including those that center on Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity Expression (SOGIE) awareness and trans representation in Philippine media.

In this review, I’ve written about Pelikulaya’s selection for its short film competition. Streaming the films based on how they are curated by the FDCP channel, the at-home moviegoing experience leaves one a sense of satisfaction, despite the eclectic mix of exciting and middling works.

Here are insights on all ten films in the roster:

Mga Kuan (2022; dir. Jermaine Tulbo)

In Mga Kuan’s opening sequence, a team of reporters, I suppose, sets out to locate the Diosnon residence – a residence of “bizarre things,” according to hearsay. Upon reaching the house, the reporters meet single dad June, who wants to throw his son Andoy a big surprise on his eighteenth birthday. But Andoy refuses the celebration because the party goers (his neighbors) have prejudice against him. These people consider him bizarre due to his sexuality and his late-night hookups.

Director Jermaine Tulbo relies on a talking-head style, flashbacks, a Mariah Carey reference, homemade videos, and characters whose heads are literally made out of eyes – quite a lousy metaphor – to convey the film’s emotional core as well to provide depth and impact. What the film achieves, however, is hardly a touching story about familial relationships and acceptance. Even the humor, if any, barely registers. Granted, the intention is there, but good intention alone cannot make a film hold water, especially for a premise that has been explored many times over.

Cut/Off (2022; dirs. Von Victor Viernes & Sean Russel Romero)

It takes nearly six minutes before one can hear a word uttered in Cut/Off, and it’s nothing but a scream. The rest, utter silence. But this is exactly why the film works, no matter how convenient it is to reduce the film into a coming out story.

Directors Von Victor Viernes and Sean Russel Romero understand that cinema hinges on, first and foremost, visual language. So the economy of words lends the film not only an effective filmmaking but also an effective storytelling. The deliberate control of sound builds tension and atmosphere, revealing the consequence of every move, of a simple eye contact. This artistic choice also dictates the pace, allowing the film to take shape and lay bare its pieces at the right moments.

But it must be said that the success of Cut/Off also rests on the shoulders of Vince Aseron, who plays the lead character. Aseron’s propulsive on-screen presence carries the film’s emotional beat and creates a nuanced performance out of Chris and Tina, aware of when to set up and tear down his walls.

However, the film’s ending could have been stronger and tighter had it concluded at the ten minute mark when Aseron’s character, in full drag look, stares into the camera – a sweeping moment that ties the film’s loose ends and leaves the audience something beautiful and powerful, as if to say look!

Cut/Off is a prime case study of understanding the confines of the short medium but not being limited by it.

as if nothing happened (2020; dir. JT Trinidad)

At the heart of as if nothing happened is a persona that reads an unsent letter, or perhaps a prose poem, to an anonymous recipient. One can argue that this film belongs to the “cinema of longing.” For the sad and horny. And had I seen it some X years ago, I would have totally latched on to it. But now, I’m not exactly sure.

This set of images, beautiful as they are, winds up as just that: images put together like Jenga pieces to make a whole, or at least an impression of it. These visuals also come secondary to the text, which limits its potential. What other way to make sense of the film than what the narration provides?

There is also the tendency to be literal-minded. For instance, when the persona reads the line “feet, arm, chest,” the director could have offered images that evoke the feeling of embrace and warmth. Instead, what we have on screen is the exact equivalent of such body parts.

Even the text itself, poetic as it is, hardly delivers something new. Depth is sacrificed for the sake of effect to the point of tedium, as though nothing really happens. But it shouldn’t hinder one to treasure this piece on a personal level, which obviously its impetus. This is to say that I still look forward to what Trinidad has in store.

Kubli (2022; dir. Jam Navalta)

It is easy to deduce the conceit of Kubli just by knowing its title, and what a grating experience to see it unravel and succumb to literal-mindedness. It doesn’t have the eye for subtlety. Because what we get for a story about a queer individual hiding in the closet is that person literally being in the closet. How unimaginative. Its pace and tone are also a magnet for mishaps. As if that were not enough, we also had to endure a long, winding scene where the lead character met his self-righteous neighbor, a scene marred by platitudes and excesses – acting, direction, and script. It would have benefited the film had it actually hidden something for the viewers to ponder on. But it seems like its idea of getting the message across is to over explain.

This Is Not A Coming Out Story (2022; dir. Mark Felix Ebreo)

This Is Not A Coming Out Story is a sight to behold, thanks in large part to Juan Pablo Pineda’s production design, Harold Lance Pialda’s cinematography, and Miguel Ramos’s editing. Complemented by Mark Felix Ebreo’s brilliant direction, which speaks of his grasp of the form, these elements work together to depict a lighthearted yet painful story of discreteness in this gay age of Grindr and hookups. The film intimately captures the awkwardness of first encounters and the interior struggle that comes along with it, even when one feels the stakes could have been raised higher. AJ Sison and Jel Tarun know their way in front of the camera, so it’s no surprise that their tandem brim with chemistry. As the title elicits, the film ends with an admission: coming out of the closet is still more taboo than norm, despite claims of progress in the queer community.

We Were Never Really Strangers (2022; dir. Patrick Pangan)

If there is one thing I’m particularly grateful for in this year’s Pelikulaya, it’s introducing us to promising actors like AJ Sison, whose darling on-screen presence is enough reason to put a smile on one’s face. Like many brief encounters, We Were Never Really Strangers comes off as something very specific to that feeling, yet still manages to find texture in it, capturing in the process the pathos embedded in films of its ilk.

However, the obvious references of this short cannot be denied. For instance, the scene where the lead characters share a kiss on a bamboo raft while dipping in the river is reminiscent of Mischa Kamp’s 2014 film Jongens. Of course, one cannot overlook the gays-on-bike trope – a staple in many queer romances, such as in Daniel Ribeiro’s 2014 coming-of-age drama The Way He Looks.

But what I admire in We Were Never Really Strangers is its close gaze of the male body, its cunning ability to capture it in a way that is never intruding, evoking a sense of familiarity amid the strangeness, as though we’re looking at a decaying yet beautiful canvas. Despite the film reveling in sentimentality, magnified by its subdued tone, it’s still a delight to watch.

With his unique Kapampangan voice and vision, Patrick Pangan is a young, emerging talent to watch out for.

Second Gear (2022; dir. Christian Angelo Cruz)

It goes without saying that Second Gear needs more than a second gear in order to work. Look, I honestly don’t mind the low-budget animation, but my main problem with it lies in how the film miserably lacks the concept of perspective to the point that it becomes a struggle to figure out who is saying what. Many times the dialogue doesn’t match the image, disrupting the film’s flow. Still, I’m glad to have seen that the festival provides a space to queer animations like this, which remains scarce in local cinema.

Kung Sa Diin Ang Suba Tarabuan (2022; dir. Seth Andrew Blanca)

Kung Sa Diin Ang Suba Tarabuan’s use of a single location and its lack of color only become interesting if one accepts that they are used to create a certain mood and character the film wants to achieve so badly. But there is hardly anything to anchor it to because its emotional heft barely translates on screen. That there exists a romantic relationship between the two female leads registers like a mere contrivance. They can be close friends at best, one might venture to say. And it’s either an issue of chemistry or lack of depth. In the end, the film’s core, if any, ebbs away like a river long abandoned and forgotten.

Baklaak (I’m Gay) (2022; dir. Gabb Gantala)

Following Maris (2020), Gabb Gantala seems to have a penchant for producing films under three minutes. It’s either he strives for brevity or he lacks the imagination to extend his works a little further. In Baklaak, a portmanteau of the words bakla (gay) and ako (I/me), the director, as the logline warrants, relies heavily on monologue to convey the film’s thesis. Predictable twist aside, the film manages to offer something about how children are not only often misunderstood but also marginalized.

But what more if they are queer? Baklaak is addressed to adults as much as it is to children, revealing how the power dynamics between the two often breeds dated beliefs and a culture of exclusion, especially in terms of discovering one’s gender identity at an early age.

Nang Maglublob Ako sa Isang Mangkok ng Liwanag (2021; dir. Kukay Zinampan)

Nang Maglublob Ako sa Isang Mangkok ng Liwanag is the perfect way to conclude Pelikulaya’s short film competition as it is the strongest work in the roster. It’s not my first time to have seen this film, and my sentiment still stands that it’s one of the cinematic gems of 2021. Yet, it’s sort of an injustice to call this piece a product of the pandemic because it offers so much more.

Poetic and sensual, Nang Maglublob Ako taps into the fiber of trans/queer struggle – stories that largely remain on the periphery of cultural conversation, stories stereotyped at best. In the film, we witness how Sunshine and Frena navigate two weeks of isolation, documenting how quarantine restrictions impact the queer community beyond physical sense, how it strips them of crucial parts of their identity, and how trans folks have long been denied of inclusive spaces.

However, the film’s emotional pocket, enhanced by a beautiful soundscape, stems from the fact that Zinampan’s ideas are not born out of thin air. Nang Maglublob Ako captures the director’s personal encounters with queerness, but it doesn’t hinder the film in offering a universal truth, which unveils how grounded of a filmmaker Zinampan is. It’s fitting that it took home the festival’s best short film award.

With this cinematic language and arsenal, I’m excited for what’s next for Zinampan. I firmly believe we need more local queer voices that truly evoke what trans cinema and Pride protests mean.

Pelikulaya Film Festival ran from June 10-26, 2022. Visit the FDCP page for more info on films and events.