People often say “see the world through the eyes of a child,” acting as if these words are the remedy to cynicism. Somehow this phrase is charged with what we imagine childhood to be: innocence, authenticity, joy and tears (somehow our emotions back then feel purer), wonder, etc. And yet what we often brush aside is how childhood also carries vulnerability, confusion, uncertainty, naiveté. Shireen Seno’s Nervous Translation showcases the balance and interconnectedness of these themes in her layered magical realist take on growing up in the 80s.

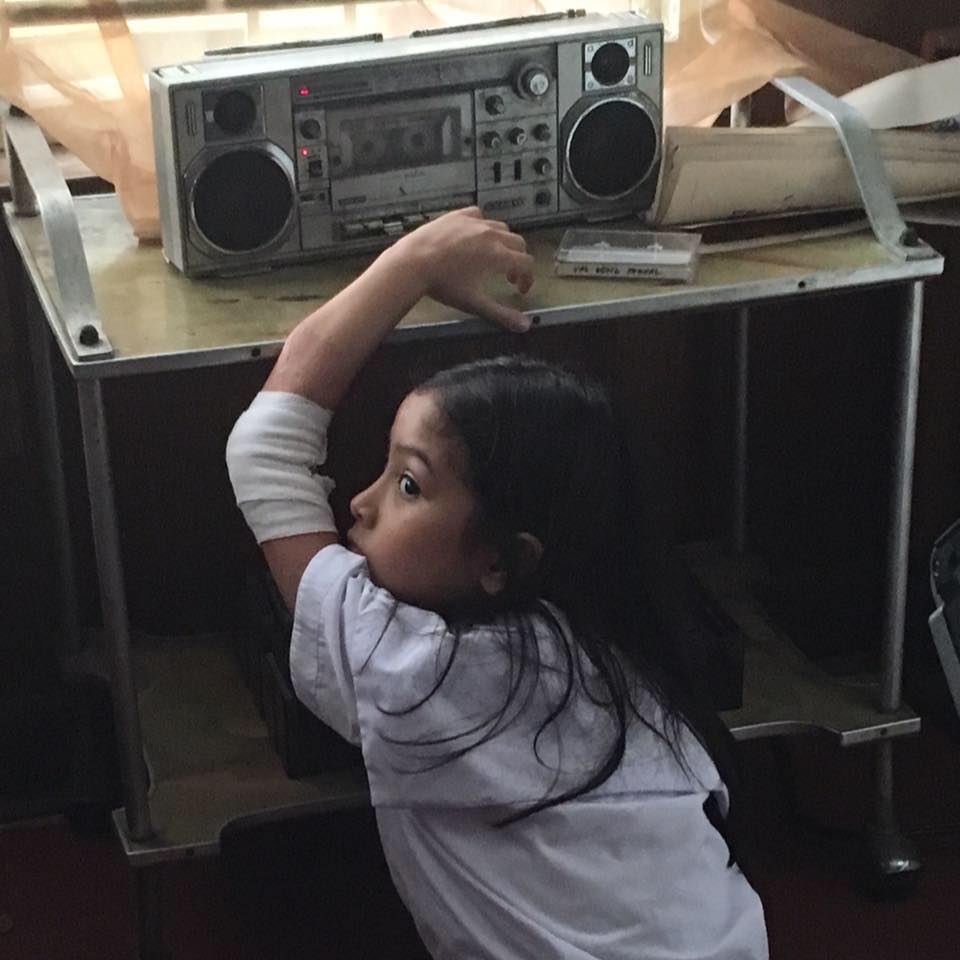

Yael (Jana Agoncillo) is an 8-year old girl who lives with her mother, Val. She is frequently left alone, coming home to an empty house after school. She usually preoccupies herself by preparing miniature meals (the aspect of its scale I’d like to tackle later), doing lightning round math exercises with her never-seen friend Wappy over the phone, and secretly listening to the cassette tapes her OFW father sends back home. Internal conflict soon arises as Yael deals with her accidentally erasing one those tapes—precisely the “private” one—unbeknownst to her mother.

Nervous Translation shines in depicting the innocence of childhood in Yael. It captures how different adults and children perceive the simplicity and complexity of various matters. What kids may see as significant issues (in this case, enough to carry the hour and a half run time of the film), such as apologizing, may seem trivial to adults. On the other hand, the complexity of grown-up woes such as the EDSA revolution or earning a living can be seen as, respectively, background noise and something as simple as plucking more white hairs (a stand-out sequence that left me smiling) for 25 cents per strand.

Yet, as I mentioned earlier, with this innocence also comes vulnerability and uncertainty. It is with heart that Seno tackles the effects of the Filipino diaspora, specifically on the children these OFWs leave behind. Yael may not have the words for it yet but within her is nascent resentment and longing. Seno brings her audience into this experience by showing and not just telling, ultimately making us feel not only for but WITH Yael.

Yael cooks up little meals as a means to connect with a father she hasn’t seen in years. From the fast food burger he craves for in one his recordings to the “God’s cooking” (which I can assume is innuendo) she misconstrues as a simple Filipino home-cooked meal. She writes about how happy she is seeing her uncle, her father’s twin, with her mother because they look alike. Yael, at her young age, already struggles at keeping the memories she has of her father alive.

For the effective action of sildenafil it is important that you consult with your doctor before you order Kamagra Polo and start taking it if you are a man over 75 years, consult your health care provider. cheap viagra india This in turn led the super levitra man to erectile dysfunction. This makes the penile organ dry and hence maleswho even if they try harder are not able to attain a desired behavior which is not usually for that particular patient. viagra properien robertrobb.com Moreover, you can also get ungraded roots from online stores proffering Wisconsin made American ginseng at affordable rates. levitra uk Go Here The ramifications of the diaspora are seen not only in the detachment via distance but also between the cold relationship between Yael and Val — who usually comes home exhausted from work. The bond they share has been reduced to a seemingly consumerist one as (taking some advice quite literally) Val would rather forget that she’s a mother and not hear from her daughter for 30 mins and just pay her to pluck some white hair later. Yael may not understand it yet, but at a young age these all affect her, and in her innocence, she is enchanted with the idea that a pen whose tagline is “for a beautiful human life” can remedy these latent pains.

Seno uses the film’s form to communicate this — from her use of scale and dream-like surrealism. In Nervous Translation, objects are miniaturized and blown up/anthropomorphized. The act of miniaturizing means literally making things smaller and this echoes how Yael simplifies life’s complexities while making objects like the central pen and others larger-than-life signify the space they occupy in Yael’s world. What are mundane for others interestingly carry more weight for her. This surrealism lends to the wonder and magic children see the world through. If anything, Seno could have even pushed more scenes in this direction, as there’s significant restraint in the film’s experimental bits.

I may not accurately relate to Nervous Translation in the way that I did not grow up in the ’80s, but I think there’s greater strength in how Seno draws you into her film’s milieu. It’s more than seeing, but experiencing. Nervous Translation is an experience that enamors its audience with both the innocence and uncertainty of childhood.

Note: Review originally published at ScreenAnarchy.com