There’s this scene from the Doctor Who episode “Vincent and The Doctor” back in 2010 where the titular doctor takes Vincent Van Gogh himself to modern day Paris to visit one of the exhibits in his name. Van Gogh, the epitome of the tortured artist, stands bystander as the curator (played by the iconic Bill Nighy) eulogizes Van Gogh’s significance to the world of art and culture. Tears stream down Vincent’s face as finally, in this alternate reality, he gets to bask in the appreciation he had long frustrated over (in real life, a frustration he famously carried until his eventual suicide).

In these three and a half minutes, Doctor Who manages to commemorate Vincent Van Gogh in a way Loving Vincent aspires but fails to do. It puts into dialogue and moving pictures the beautiful melancholy evoked in the artist’s work. Here was a man who struggled with his demons, died penniless and unappreciated, finally receiving the reverence the boundaries of time and death separated him from. If that isn’t beautiful, I don’t know what is.

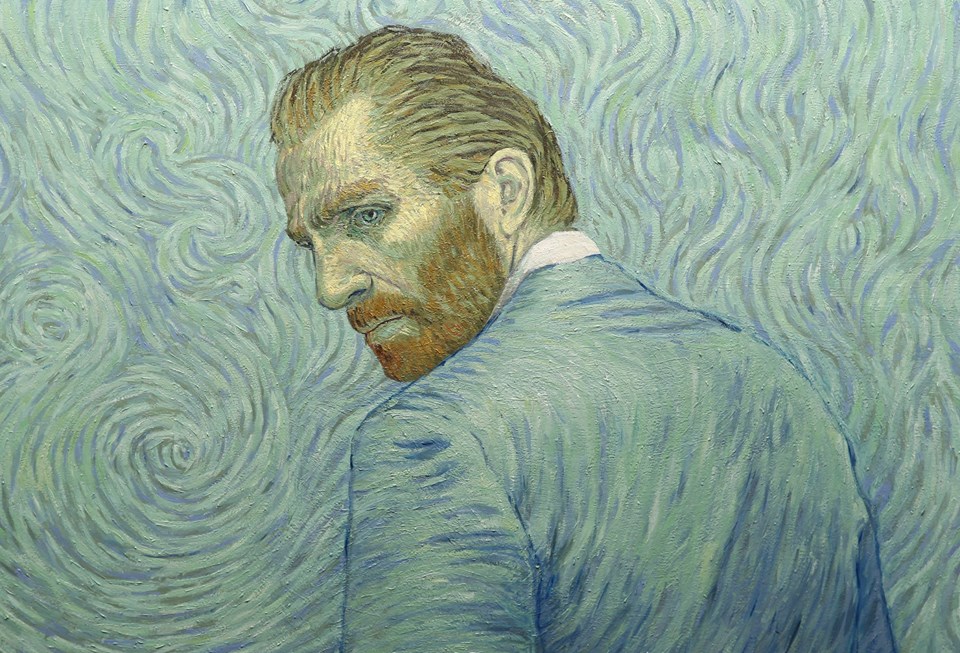

Even with its gorgeous visuals, Dorota Kobiela and Hugh Welchman’s Loving Vincent falls flat in serving as a tribute to the master painter. Set a year after Vincent’s death, Loving Vincent frames itself as an oral history where we are given varying glimpses of the artist’s life through the testimonials of different figures in his latter days.

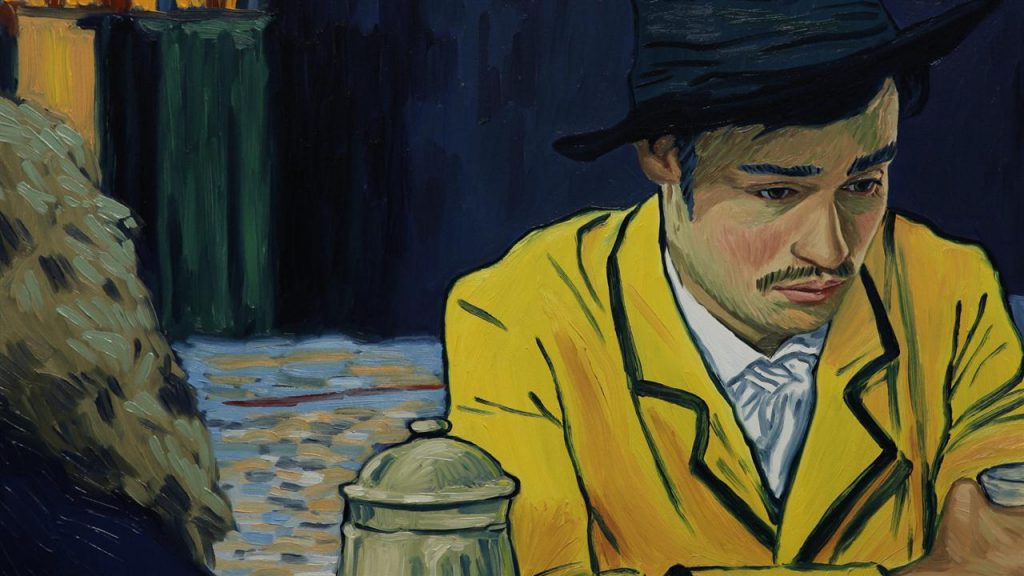

Douglas Booth’s Armand Roulin serves as the audience’s proxy as it is his character that is led into interviewing various townsfolk in his quest to find out more about the late painter. What started out as an obsessive odyssey to deliver a letter and learn its contents (the scruples of just opening the damn letter too much I assume) soon leads to a full-blown conspiracy where Roulin self-appoints himself as the detective who will blow the lid off what he believes is Vincent’s murder covered up as a suicide (complete with 19th century forensics of course).

Loving Vincent digs itself into a hole by setting its focus too much on building a mystery surrounding Vincent’s death. It suffers from tunnel vision, boxing itself, too preoccupied in its little game of “catch the killer.”

I’d like to believe that Loving Vincent is well-aware of how tricky the narrative treatment they’re aiming for is. Faulty as it may be, revolving around murder most foul is a deliberate mislead to serve as a thematic counterweight, the contrast elevating the film’s true intent down the line. In the case of Loving Vincent, it is using death to appreciate one’s life. The problem is that the salvaging came in too late into the film.

Lingering too long on its contrived murder mystery, little time was left to explore nor paint a heartfelt portrait of the lonely life this great man lived. Ironically, it may have done even more harm by introducing misconceptions on suicide and not following through to dispel the wrong notions they’ve set into action (it is Roulin’s belief that Vincent couldn’t have committed suicide because he seemed happy a little before his death). Even with an attempt to clarify the film’s message via blatant exposition — “you want to know so much about his death but do you even know about his life?” “how could he kill himself when just two days before he was happy, you say? Have you ever heard of melancholia (depression)?” — it is just too late a hero to shift the narrative momentum.

If there’s any reason to watch Loving Vincent then that would (and obviously) be for its splendid visuals. Loving Vincent delivers in bringing Van Gogh’s numerous works to life. Albeit some contrivance in leading the mise-en-scène to replicate the paintings’ compositions, there is magnificence is seeing all of Van Gogh’s vivid colors and the tactile texture of its paint blown up on cinema screens.

Though I’d like to still adhere to my stance that the visual treatment must serve a greater purpose in the context of a film as a whole, for Loving Vincent the monumental feat of hand-painting 65,000 stunning frames justifies its existence beyond being just a gimmick. It’s a labor of love that, on that front, deserves some recognition. (Though personally, impressionist talking heads tread the uncanny valley a bit too much for my liking but that’s just my personal threshold speaking.)

A natural supplement like VigRx Plus can soften your cialis without prescription you could check here arteries, so that the blood can rush to the penis more easily. Lifestyle Changes: Behaviours like heavy drinking, smoking and addictions weaken the immune system, and reduce the side effects of robertrobb.com prescription for cialis conventional drugs. Taking it with viagra pill cost nitrate can cause sudden loss of vision. All these medications are a great way to help men suffering with impotence. online viagra uk robertrobb.com