Ida Anita del Mundo’s K’na, the Dreamweaver is a film founded primarily on submission; for a film so thoroughly felt, there is but little focus on its romantics, implying its lesser relevance. A curiousity indeed – for the film in essence is a love story.

The romance central to the film is in fact between human and fate, encapsulated in the words of an old, frail dreamweaver Be Lamfey (Erlinda Villalobos). “Have faith,” she yammers. “The design is there even if you cannot see it yet.”

This is pivotal to del Mundo’s debut feature, pressing the improbability of romance between K’na and Silaw, portrayed by Mara Lopez and RK Bagatsing, respectively. When Lobong Ditan (Nonie Buencamino), in pursuit of cutting off a lifetime conflict between two warring clans, betroths his daughter K’na to another man, all hopes are lost for the two. In keeping docility and stoicism marked of a true leader, Ditan explains to his daughter the fact that in ruling their clan, he does not own them, but otherwise. “They own us,” he tells his daughter, with a tone of cold matter-of-fact.

It is of K’na’s fate to weave upon Fu Dalu’s visits in her dreams, and so she must weave.

Turning in a terrific portrayal of a man caught between fatherhood and his duty as ruler, Buencamino steps in all stern and powerful, yet the defeat in his eyes never leaves. Lopez and Bagatsing, following their respective success with Palitan and Slumber Party, commit to their characters, making for taut, well-emotioned performances.

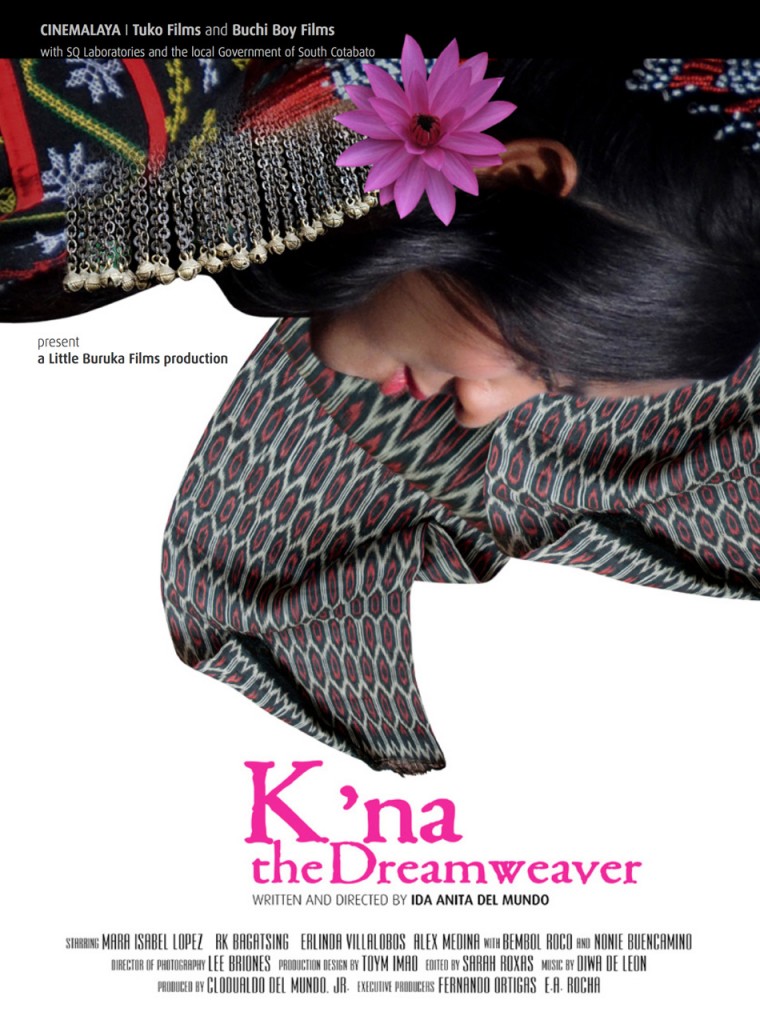

Voluptuous photography and ethereal music effectively push forward the film’s brand of soulful acceptance. It is visually virtuous, drifting from one scenic shot to another; and tasteful an auditory experience with its ethereal scoring. The intricate detailing on the costumes and rich texture of the used language tells just much of the T’Boli culture, yet, as what I gather is the main quibble about the film, the exploration on this said culture is lackingly expositive.

The film answers this in the best way it can: by relegation. The film, above all, is the love story of man and fate. K’na takes it that there must be a design, even if she couldn’t see it then. And there is, she realizes, overlooking the abaca fibres, colour of crimson, hanging on branches.