Embryonic dormancy

Seeds take time to burst out of their coats, push off the overlying soil on top, and be christened as the plant they ought out to be.

Binhi (The Seed) takes your patience to establish its suspense through slightly jittery long-take tracking shots, which unfortunately frequently end with a dud. It builds up the horror within sequences but fails to add to the over-arching dread. After the first hour, we don’t progress from the repetitive visualization on the haunted house it portrays.

Even with the regular monotonous disappointments, Binhi is more interesting with its calculated visuals and characters. Grounded by a succint location choice, Erwin Sanchez‘s production design stands out thanks to the soft, unobstrusive lighting while highlighted by the dynamic exploratory non-nauseaous camera movements from Pao Orendain. The high altitude of Baguio, which avoids the harsh sunlight for production purposes, offers a different culture of a Philippine city most moviegoers would be accustomed to. Such rich setting, amplified by its endearing display, is minimized with the disengaging origin of the spirit’s mild malevolence. From the get-go, there is no elaboration of the spirit aside from offering cheap scares to zero effect. There are no hard clues for the audience to mine for nor to conjure their own hypotheses. It makes sense in the end, after the obligatory reveal that the unmentioned sets up the characters’ current situations and propels the plot forward. However, the effort in emphasizing the spatial location is put to waste, or a possible red herring at best.

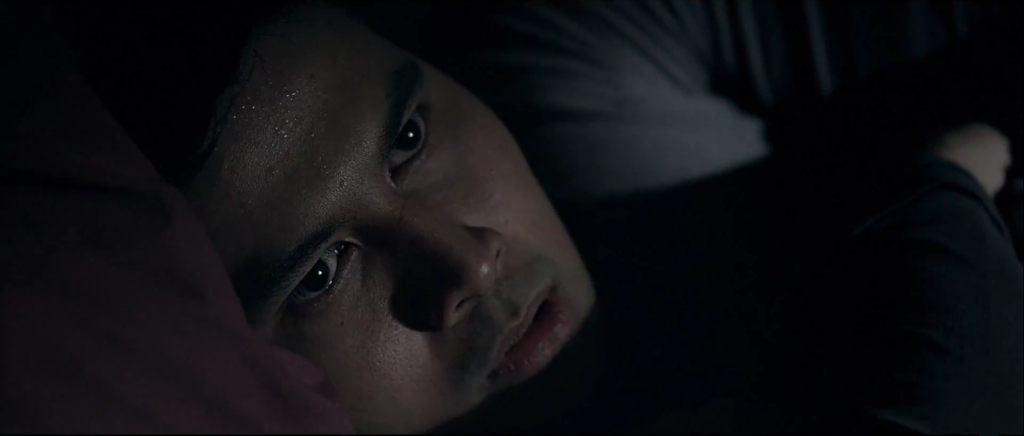

The other compelling part of Binhi is the swell acting from the lead couple, Baguio-born Daniel (Joem Bascon) and his very pregnant wife Cynthia (Mercedes Cabral). The mature chemistry they evoked is a comforting sight against the wearisome nature of the horror the movie purports. The horror film could have been treated as a relationship drama as there are seeds thrown in to strain the couple’s marriage. A shouting match, even if sounding cliche, might make the tension more palpable instead of solitary expressions of their fears, or the downright exposition through unnatural dialogue. Without these additional portions, improving Cynthia’s response to the paranormal phenomenon is the simplest remedy to advance the seed’s growth. It is noted in the latter part of the film that she sees and feels the disturbance differently, and opposite to what other people have experienced. If employed earlier, there will be variety to the jump scares and more depth to both the relationship and horror constituents of Binhi.

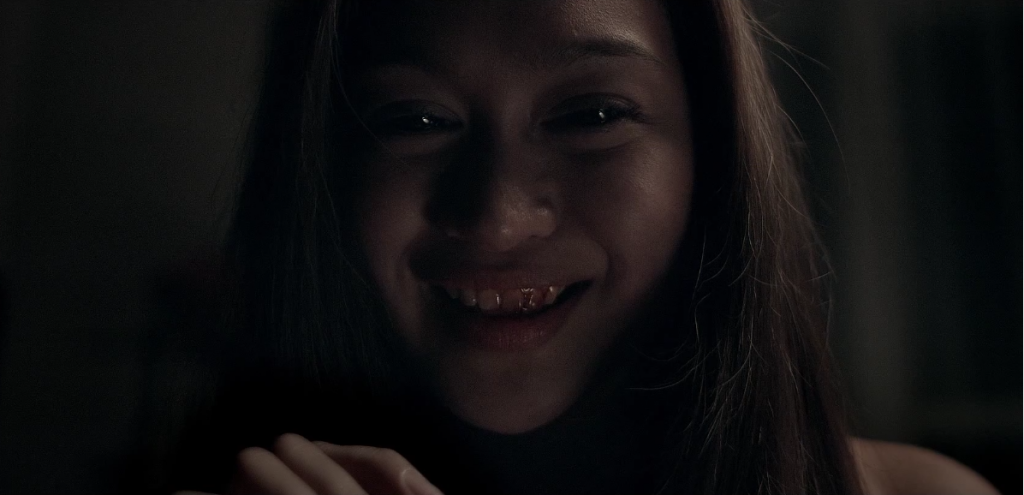

Despite all these, the extremely satisfying bits come in the end. Reminiscent of Koji Shiraishi‘s found-footage Japanese horror films, the shift in style adds the flavor of horror anticipated since the very beginning. The final shot in this weird but lovingly creepy penultimate sequence could have closed the film on a better, even if absurd, note. The finale is still acceptable given Binhi‘s more realistic form but it could have gone out even smoother if it weren’t for a meddling archetypal mid-credits scene.

As an afterthought, Binhi is best appreciated as a reference for studying, or the colloquial peg, for its cinematic technique, interior design, architecture, lighting and color theory. It definitely won’t give the lasting chills or atmospheric suspense the audience typically seeks. Ultimately, the aesthetics all turn out superficial, purposeless and even weighed down by the generic cringe-worthy score, the clunky support, and the story’s dormant seeds scattered across its hollow core.