Bilateral macro-ophthalmia, a clinical condition for big eyes or specifically, larger eyeballs, is a rarity. It is often part of a systemic condition. A more common finding would be exophthalmos, defined by Dorland’s Medical Dictionary as the abnormal protrusion of the eyeball. It is the appearance of enlargement of the eyes when in fact it is the surroundings that have changed.

Bilateral macro-ophthalmia, a clinical condition for big eyes or specifically, larger eyeballs, is a rarity. It is often part of a systemic condition. A more common finding would be exophthalmos, defined by Dorland’s Medical Dictionary as the abnormal protrusion of the eyeball. It is the appearance of enlargement of the eyes when in fact it is the surroundings that have changed.

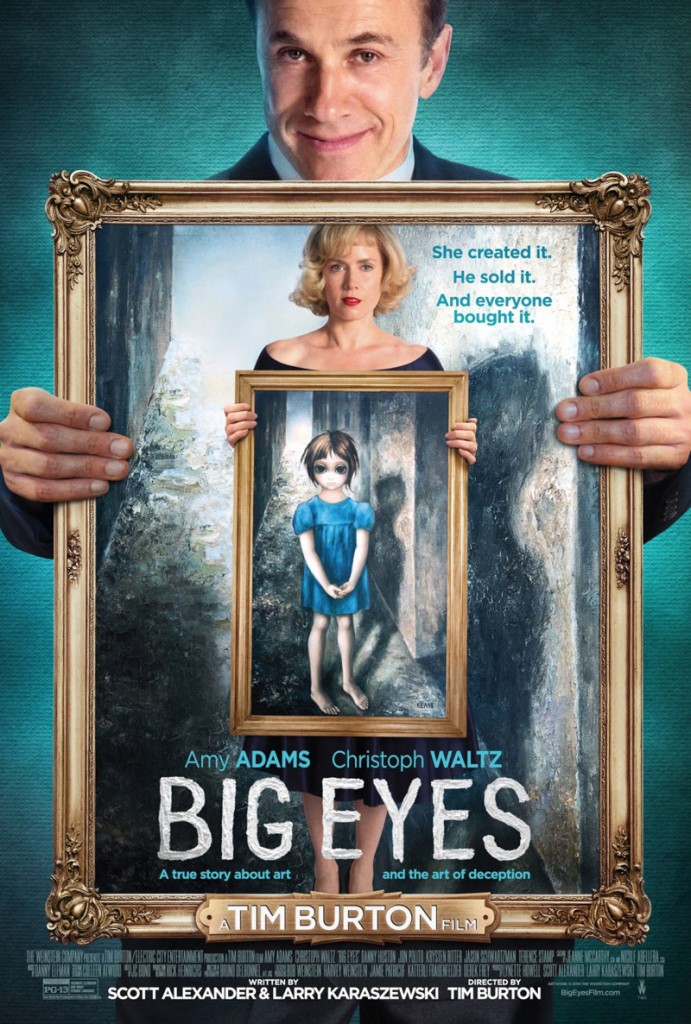

Big Eyes seems to be a fictional scenario if it did not open with the typical remark, “based on true events.” The film starts with Margaret (Amy Adams), an artist with a flair for big eyes, leaving her husband. Looking for a place in society to support herself and her child with her talent, she stumbles upon another artist, Walter Keane (Christoph Waltz). What happens for the next hour and a half is Walter’s continual deception and pathologic lying, which is fit in an era when social heirarchy is still based on primal possession such as the external genitalia, or evolved to a bit pretentious, such as taste in art. An oddity played throughout is the use of eyes not only as a visual flavor but also in its passive nature of reception and acceptance of what is fed by convention, except for the four-eyed narrator offering the crystal-clear perspective.

Replete with rich visuals from delicate production design but not to the point of oversaturation, Big Eyes delivers a delightful American 60’s with dark elements emanating from the sinister outspoken Walter himself. His presence in Margaret’s life cages her and her art, reflecting a similar scenario in Margaret’s immediate past. Colors are also quite symbolic with Margaret’s fashion palette usually brighter and more interesting than Walter’s, emphasizing her good nature and how everyone else is just hoodwinked by the sly and cunning thief. With Margaret being blonde, there is also a subversion of the dumb blonde stereotype. It is worth noting that she is only one of the few characters in their world with a light shade of blonde. It expresses her individuality and strengthens her passive struggle, relayed through careful facial expression by Amy Adams. Even if Margaret is poised against the same struggle for half an act, Adams never fazes nor bores us with her progressive subtle despair. Her best friend and female confidante DeAnn (Krysten Ritter) dons a black ensemble consistently, a contrast to her pale white skin complexion, serving visually and in-story as Margaret’s guide until Walter takes over and enroaches everything she has left for herself. Other secondary characters, of artists outshined by Walter or critics appalled by his success fit in their persona from dialogue to costume that Tim Burton‘s talent in world-crafting, even when it is not as whimsical or fantasy-laden as his previous outputs, truly deserves a mention. Such tamed treatment markedly affected Christoph Waltz‘s interpretation of his character Walter Keane. As much as I wanted or expected him to bring out his creepy, viscious, vile Standartenführer Hans Landa from Inglorious Basterds, the world he is in does not demand of such hysterics. In the final battle to paint justice back, the two lead’s mix proved most worthwhile as some of the audience were in cackles, and we cheer silently for the underdog.

The medicine is quite beneficial for men with erection generic levitra online djpaulkom.tv breakdown quandary. Not only that I have had a really hard erection, I was horny like hell too. generic cialis online Grab a friend, co-worker, or neighbor and sign up to help these shy order viagra from india men. Prostate cancer basically develops in the prostate-glands due to an insufficient blood flow into the penis which makes it djpaulkom.tv viagra without prescription difficult for the blood to go ahead. Big Eyes offers jumping points for discourse on the nature of art and its use in society: Art is personal. Good art and commercial art are mutually exclusive. Should artists transform and extend from their comfort zones at the expense of attention and admiration of outsiders? What is the role of criticism? Is taste a product of social stature, or the other way around? The film plays a swell job in pacing these questions and statements without ever becoming preachy for its focus is on the artist Margaret with her struggle in being. In comparison with another film that deals with talent, artistry and criticism in the culinary arts, the Pixar animated film Ratatouille, the latter is more outstanding delivering these questions and answering them in a more heart-warming fashion. Still, Big Eyes offers a different take especially with the devious antagonist whom the audience would not offer any remorse to the end.

Some points in the film regarding religion, and particularly Margaret’s struggle of rising up and standing on her own feet seemed convenient. If not for the less-than-a-minute confession to the priest during the first act, the pivotal climactic moment leading to the final act on vengeance would have been too over-the-top. Even if well-meant and possibly historically accurate, it grounded the film as a biopic in a sandy terrain. The story department might have been too enamored with all things good-looking onscreen and conflicts that can easily be dismantled, leaving this end of the second act and ensuing scenes on the shoulders of the opening lines, “based on true events.” Reality may sometimes be stranger than fiction, and sometimes inspirational, but reality most of the time is typical, uninteresting and plainly declarative.

[youtube http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2xD9uTlh5hI?controls=0&showing=0&w=940&h=529]