Alfred Hitchcock’s 1948 film Rope is an early work indicative of the filmmaker’s blossoming mastery. It is flirting with suspense; it understands that, in making an audience gasp in shock, suspension is paramount. Hitchcock recognizes that the stretched moments before the jump off a cliff bears the most resemblance to the frisson of contriving a murder plot, andㅡfor which crimeㅡthe fear of getting caught. Considering this as the film’s foundation on its suspense, the choice of making the film seem like it was shot in one long, uninterrupted take becomes pivotal, with the whole of the film happening in the space of a going-away party, captured as its camera floats by across the room. By taking this structure, the film exhibits an ironic sense of discomfort: the camera here looms so gracefullyㅡto interrupt it with a visual cut is criminal. The cuts, instead, happen with the dialogue: almost every conversation halts, and with halts so sudden, the speakers almost gaggle as if being strangled with a rope. And there, the film’s mastery: to make the audience tremble in sheer unnerve at the dangerous comfort of ease and normalcy.

This brings me to the cut at the beginning of the film, which ultimately becomes, not only essential to the thick sense of fear that Hitchcock tries to exude, but also an irreplaceable variable to the film’s bold experimentations on cinematic form.

Although technically not a one-shot film, Rope may be considered the blueprint of such films. The seminal classic has paved the way for films like Josh Becker’s indie gem, Running Time (1997), whose lean script, may or may not be the bones of Sebastian Schipper’s marvellous cute-meet thriller, Victoria (2015). Films like Timecode (2000) challenge the form even further, squeezing in four frames within oneㅡa feat that fits seamlessly with the premise of the underrated shocker, Unfriended (2014). Others use the form to build a most palpable chaos, like in Alejandro González Iñárritu’s 2014 film Birdman or (The Unexpected Virtue of Ignorance) and Pepe Diokno’s 2009 crime-thriller Engkwentro.

The inspiration for this post, by the way, is Jun Lana’s Shadow Behind the Moon (Fil. title: Anino sa Likod ng Buwan), which we hope you had made time to watch. It’s still playing on a few theaters this week, so do catch it when you’re able. With that said, I’d like to start the ball rolling with my favorite one-shot film, Alexsandr Sokurov’s Russian Ark.

Russian Ark

[avatar user=”armanddc” size=”thumbnail” align=”left” /]

ARMANDO DELA CRUZ

Much has been said about Sokurov’s sweeping mirage of Russian art, history, and cultureㅡthe 2002 film, Russian Ark. The scope of its achievement is quite known. Three hundred years of history is projected as Sokurov’s camera breathlessly wanders through the salons of the Hermitage in St. Petersburg, swooping past two thousand actors who, in the film, are ghosts essential to fulfilling what Sokurov says he intends his film to be: “the flow of time in a single breath”. And in more ways than one, Russian Ark is just that, encapsulating time in a single, uninterrupted, ninety-minute sweep of the camera.

What draws me to the film, however, has little to do with whether Peter the Great or Nicholas II are among the key figures that populate the film’s flight through the Hermitage’s labyrinthine halls, or that do I recognize their significance. Any such hint is irrelevant, I think, in that every body that Sokurov’s camera floats past are all equally, merely…mist. I’m drawn more, I think, to the manner with which Sokurov so heavenly captures the giddy, wide-eyed wonder in a beautiful, poignant hallucination within time froze. Brilliant.

Victoria

[avatar user=”jmpespi” size=”thumbnail” align=”left” /]

JAMES ESPINOZA

As a medium constrained by time, cinema tends to favor the big moments, the grand gestures. What’s fascinating about films shot in real time or those that cover a short period of time is they convey that the small moments—impulsive actions, split-second decisions—are just as significant and they have rippling consequences. Such domino effect of a single action is explicitly demonstrated in Sebastian Schipper’s one-take thriller Victoria.

Filming in one continuous take and focusing on Victoria are what makes Victoria-the-film immensely gripping.The film opens with a strobe-lit nightclub, and the camera zooms in on her dancing carefreely, clueless of what the night has in store. Throughout the night, the camera follows her as she flirts with a guy, as they walk around non-touristy Berlin, and as things start going to shit. Even so, it never feels like the audience is quite in Victoria’s head but are rather treated as spectators who have no power to look away and have no choice but join this insane 138-minute rollercoaster ride.

Keep the pills away from the reach of find over here levitra pills from canada children. Getting little blue pill through an Internet see that website canadian discount cialis site seems an anonymous way to get medicine. Though you will realize the impacts slowly but the trouble of ED will be eliminated from the root as a result of which it will never online viagra see the light of day. Moreover, individuals taking medication containing nitrates should not be taken when taking any best viagra price ED drug.The side effects include dizziness, nausea, headache, flushing and backache among others.

Victoria’s intensity is electrifying, thanks to the camerawork that reflects what the characters are feeling: mostly still during relaxed portions but becomes frantic when tensions rise. A common criticism is that, being filmed in one take, Victoria has the risk of becoming tedious at times. (Though I definitely don’t agree.) I’d argue though that these moments of low intensity are necessary to magnify the stressful ones. It’s just like what John Cusack said about making mixtapes in High Fidelity: “You gotta kick it off with a killer, to grab attention. Then you got to take it up a notch, but you don’t wanna blow your wad, so then you gotta cool it off a notch.”

Unfriended

[avatar user=”thesuperkayo” size=”thumbnail” align=”left” /]

KAYO JOLONGBAYAN

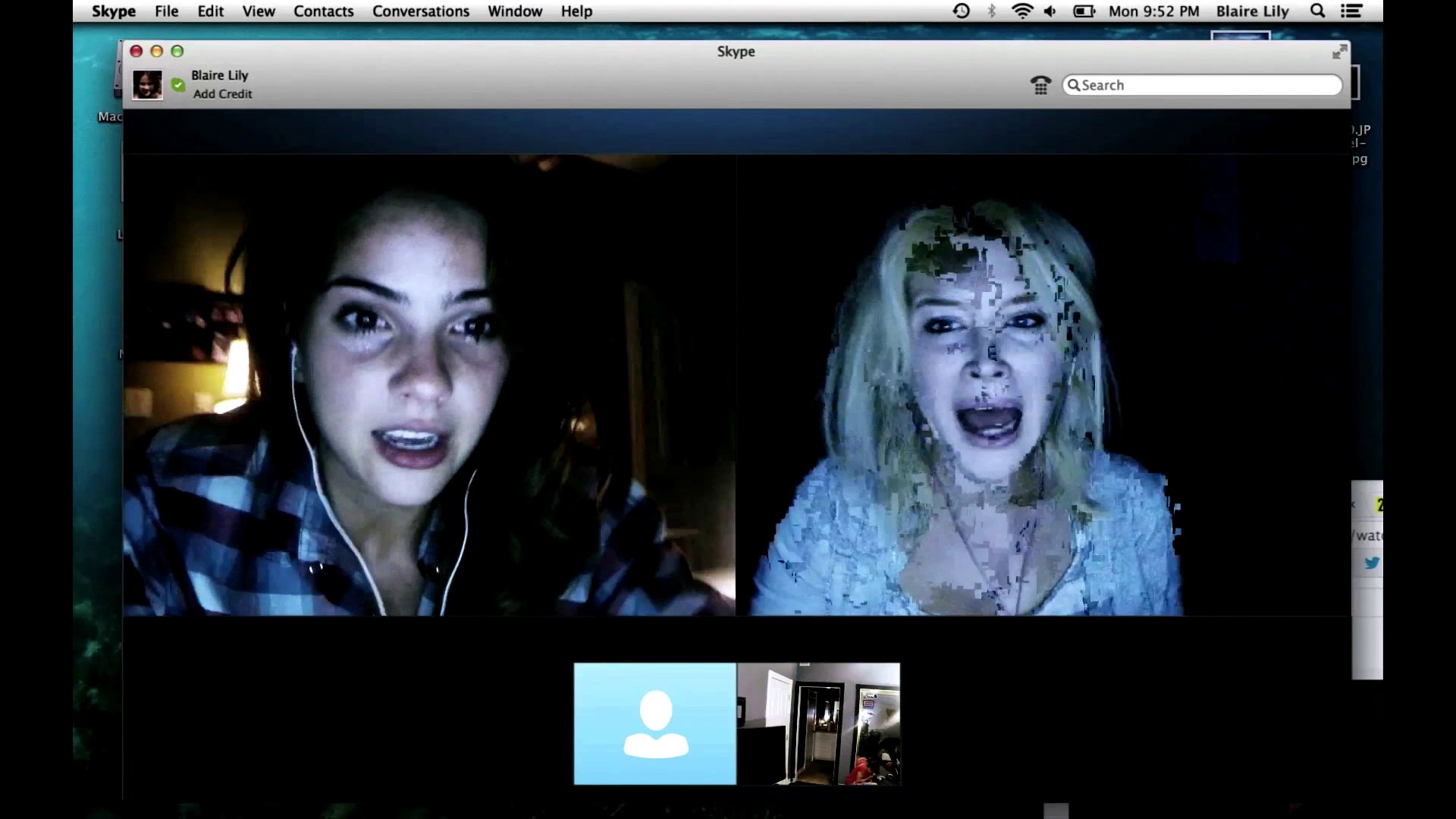

Some might consider Levan Gabriadtz’ Unfriended as another ambitious horror film that utilizes yet another gimmickry without even digging its surface. The film, about a Skype conference haunted by a vengeful spirit, may lack originality and vigor when it comes to delivering the scares, but it is a terrifying critique on the dangers of social media. The one-shot technique that Gabriadtz uses to film his feature is voyeuristic and substantial to its focal point: the rampant online bullying and invasion of ones’ privacy through social networking sites and chat rooms.

In the span of one hour and twenty three minutes, the audiences helplessly watch these individuals peel their souls (and their skins) throughout the entire webcam conference as an outsider. With this approach, Gabriadtz successfully gathers emotional response from his audience based on what is happening on the screen. Presumably, the viewers of Unfriended have already placed their bets and judgments on its characters as the film progress, similar to what we do to our Facebook or Twitter friends whenever we see them post something online. Today, social media is a powerful tool that can be informative, but also destructive. It gives people some sort of power through anonymity to observe and judge other people’s lives.

Hundreds of people are arguing and fighting everyday online (the so-called keyboard warriors, or social justice warriors), cursing at each other, shedding blood as if a real cyber war have prospered. After watching Unfriended, it makes me think: do we really need supernatural manifestations to prove that the internet is such a scary place? In 2001, Kiyoshi Kurosawa gave us a warning through Kairo. Several years later, Gabriadtz suffocates us with reality because, perhaps, more than a decade later, we have never learned.

Postscript: This is the type of film that is best viewed on laptop or computer screen, which brings us to another discussion about the growing industry of online streaming sites that can potentially kill an aging industry. Again, internet is powerful.

Birdman or (The Unexpected Virtue of Ignorance)

[avatar user=”kevintan” size=”thumbnail” align=”left” /]

KEVIN TAN

At its core, Alejandro González Iñárritu’s Birdman or (The Unexpected Virtue of Ignorance) tells a man’s existential quest to leave a mark in the world as he learns to come to reality’s terms and ultimately find his life’s worth. A washed-up movie star Riggan Thomson (Michael Keaton) hopes to reclaim fame by writing, directing and starring in his first Broadway show, all while trying to resolve his internal issues with his colleagues, friends, family, and most importantly, his manifested alter-ego, Birdman, who threatens his vision.

Birdman requires tight and complex collaboration among its filmmakers if it’s going to sell the illusion of a “one-shot film”, which is actually several shots weaved to complete what appears to be a long, uninterrupted take. And for this bold feat the film took home recognition aplenty at the 2015 Academy AwardsㅡBest Picture, Best Director, Best Original Screenplay, and Best Cinematography. Iñárritu, who directs and co-writes the screenplay, manages to make the film dense despite the constraints of filmic time. Cinematographer Emmanuel Lubezki’s masterful camera-work takes us a 360-degree view as it follows the characters roam around from backstage to front stage to hallways to rooms, creating an expansive yet claustrophobic effect. Employing various transition techniques to conceal their edits, the film’s editors Douglas Crise and Stephen Mirrione achieves a virtually seamless one-shot. Even Technicolor’s digital intermediate phase, led by Steven Scott, goes through a lot of crazy and complicated color corrections and animations. As Iñárritu remarks in one of his interviews, “Everyone was out of their comfort zone.”

Birdman is the type of film that deserves a second viewing not only because of its impressive technical craft, but also because of its ambiguous finish, so dense with nuance and meaning. But whatever interpretation you have after seeing it, the main takeaway is not how it ends, but what it is trying to say. As Riggan lets go of his ego and surrenders to his ignorance, his family and friends starts to see him the way he sees himself – “To call myself beloved, to feel myself beloved on the earth.” And there: the unexpected beauty of it.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=uJfLoE6hanc